U.S. Department of Justice

|

U.S. Department of Justice

|

1. Executive Summary

2. Study on the Importability of Certain Shotguns

3. Background on Shotguns

4. Background on Sporting Suitability

5. Methodology

6. Analysis

Scope of Sporting Purpose

Suitability for Sporting Purposes

7. Conclusion

8. Exhibits

1. Shotgun Stock Style Comparison

2. State Laws

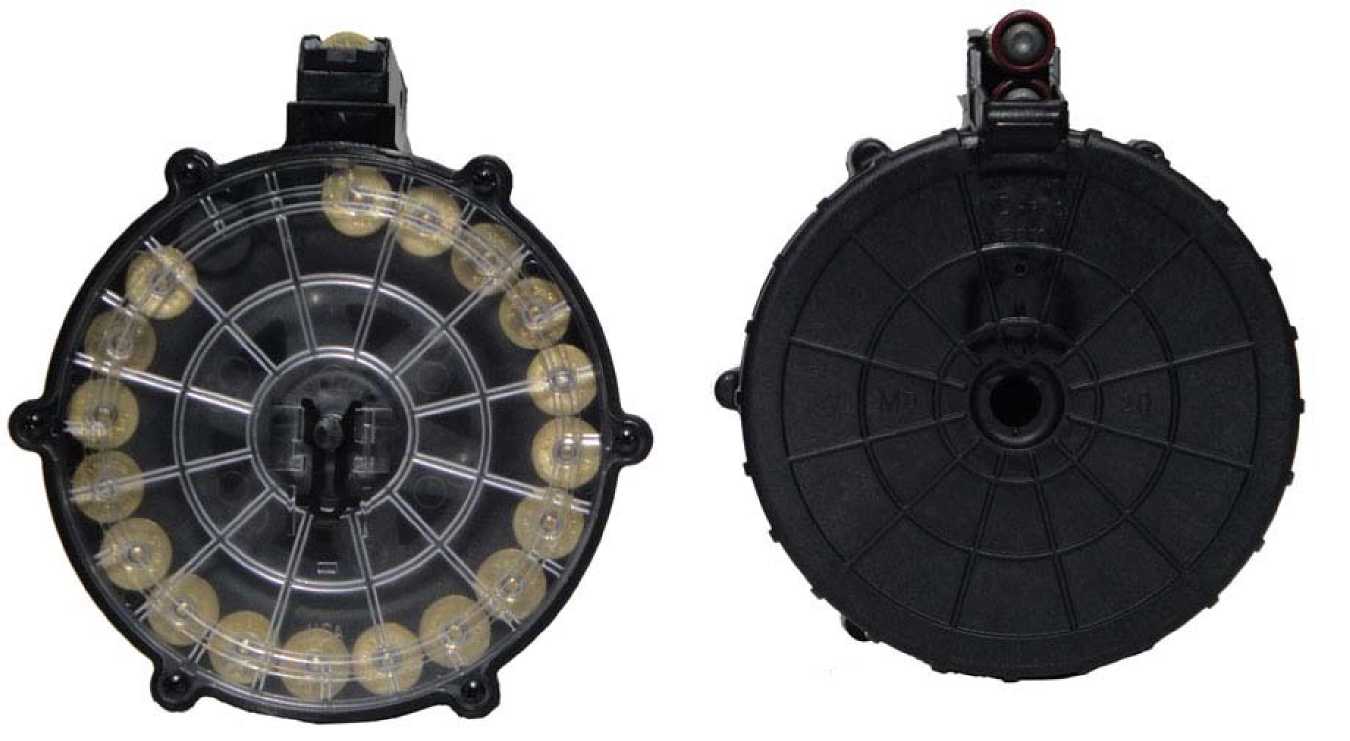

3. Sample Drum Magazine

4. Integrated Rail System

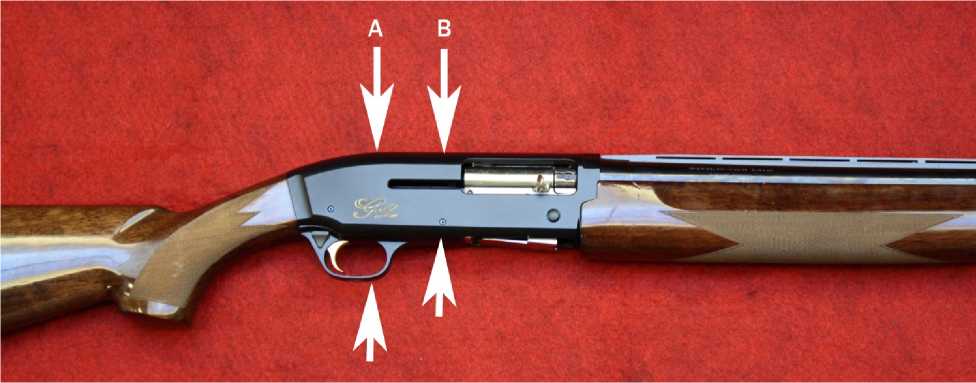

5. Bulk Measurements

6. Forward Pistol Grip

The purpose of this study is to establish criteria that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) will use to determine the importability of certain shotguns under the provisions of the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA).

The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA) generally prohibits the importation of firearms into the United States.

[Chapter 44, Title 18, United States Code (U.S.C.), at 18 U.S.C. § 922(1).]

However, pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 925(d), the GCA creates four narrow categories of firearms that the Attorney General must authorize for importation. Under one such category, subsection 925(d)(3), the Attorney General shall approve applications for importation when the firearms are generally recognized as particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes (the “sporting purposes test”).

After passage of the GCA in 1968, a panel was convened to provide input on the sporting suitability standards which resulted in factoring criteria for handgun importations. Then in 1989, and again in 1998, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) conducted studies to determine the sporting suitability and importability of certain firearms under section 925(d)(3). However, these studies focused mainly on a type of firearm described as “semiautomatic assault weapons.” The 1989 study determined that assault rifles contained a variety of physical features that distinguished them from traditional sporting rifles. The study concluded that there were three characteristics that defined semiautomatic assault rifles.

[These characteristics were: (a) a military configuration (ability to accept a detachable magazine, folding/telescoping stocks, pistol grips, ability to accept a bayonet, flash suppressors, bipods, grenade launchers, and night sights); (b) a semiautomatic version of a machinegun; and (c) chambered to accept a centerfire cartridge case having a length of 2.25 inches or less. 1989 Report and Recommendation on the Importability of Certain Semiautomatic Rifles (1989 Study) at 6-9.]

The 1998 study concurred with the conclusions of the 1989 study, but included a finding that “the ability to accept a detachable large capacity magazine originally designed and produced for a military assault weapon should be added to the list of disqualifying military configuration features identified in 1989.”

[1998 Department of the Treasury Study on the Sporting Suitability of Modified Semiautomatic Rifles (1998 Study) at 2.]

Further, both studies concluded that the scope of “sporting purposes” did not include all lawful activity, but was limited to traditional sports such as hunting, skeet shooting, and trap shooting. This effectively narrowed the universe of firearms considered by each study because a larger number of firearms are “particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to a sporting purpose” if plinking and police or military-style practical shooting competitions are also included as a “sporting purpose.”

[“Plinking” is shooting at random targets such as bottles and cans. 1989 Report at 10. 1989 Report at 8-9; 1998 Study at 18-19.]

Although these studies provided effective guidelines for determining the sporting purposes of rifles, ATF recognized that no similar studies had been completed to determine the sporting suitability of shotguns. A shotgun study working group (working group) was assigned to perform a shotgun study under the § 925(d)(3) sporting purposes test. The working group considered the 1989 and 1998 studies, but neither adopted nor entirely accepted findings from those studies as conclusive as to shotguns.

Determination of whether a firearm is generally accepted for use in sporting purposes is the responsibility of the Attorney General (formerly the Secretary of the Treasury). As in the previous studies, the working group considered the historical context of “sporting purpose” and that Congress originally intended a narrow interpretation of sporting purpose under § 925(d)(3).

While the 1989 and 1998 studies considered all rifles in making their recommendations, these studies first identified firearm features and subsequently identified those activities believed to constitute a legitimate “sporting purpose.” However, in reviewing the previous studies, the working group believes that it is appropriate to first consider the current meaning of “sporting purpose” as this may impact the “sporting” classification of any shotgun or shotgun features. For example, military shotguns, or shotguns with common military features that are unsuitable for traditional shooting sports, may be considered “particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes” if military shooting competitions are considered a generally recognized sporting purpose. Therefore, in determining the contemporary meaning of sporting purposes, the working group examined not only the traditional sports of hunting and organized competitive target shooting, but also made an effort to consider other shooting activities.

In particular, the working group examined participation in and popularity of practical shooting events as governed by formal rules, such as those of the United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA) and International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), to determine whether it was appropriate to consider these events a “sporting purpose” under § 925(d)(3). While the number of members reported for USPSA is similar to the membership for other shotgun shooting organizations, the working group ultimately determined that it was not appropriate to use this shotgun study to determine whether practical shooting is “sporting” under § 925(d)(3).

[Organization websites report these membership numbers: for the United States Practical Shooting Association, approx. 19,000; Amateur Trapshooting Association, over 35,000 active members; National Skeet Shooting Association, nearly 20,000 members; National Sporting Clays Association, over 22,000 members; Single Action Shooting Society, over 75,000 members.]

A change in ATF’s position on practical shooting has potential implications for rifle and handgun classifications as well. Therefore, the working group believes that a more thorough and complete assessment is necessary before ATF can consider practical shooting as a generally recognized sporting purpose.

The working group agreed with the previous studies in that the activity known as “plinking” is “primarily a pastime” and could not be considered a recognized sport for the purposes of importation.

[1989 Study at 10; 1998 Study at 17.]

Because almost any firearm can be used in that activity, such a broad reading of “sporting purpose” would be contrary to the congressional intent in enacting section 925(d)(3). For these reasons, the working group recommends that plinking not be considered a sporting purpose. However, consistent with past court decisions and Congressional intent, the working group recognized hunting and other more generally recognized or formalized competitive events similar to the traditional shooting sports of trap, skeet, and clays.

In reviewing the shotguns used for those activities classified as sporting purposes, the working group examined State hunting laws, rules, and guidelines for shooting competitions and shooting organizations; industry advertisements and literature; scholarly and historical publications; and statistics on participation in the respective shooting sports. Following this review, the working group determined that certain shotgun features are not particularly suitable or readily adaptable for sporting purposes. These features include:

(1) Folding, telescoping, or collapsible stocks;

(2) bayonet lugs;

(3) flash suppressors;

(4) magazines over 5 rounds, or a drum magazine;

(5) grenade-launcher mounts;

(6) integrated rail systems (other than on top of the receiver or barrel);

(7) light enhancing devices;

(8) excessive weight (greater than 10 pounds for 12 gauge or smaller);

(9) excessive bulk (greater than 3 inches in width and/or greater than 4 inches in depth);

(10) forward pistol grips or other protruding parts designed or used for gripping the shotgun with the shooter’s extended hand.

Although the features listed above do not represent an exhaustive list of possible shotgun features, designs or characteristics, the working group determined that shotguns with any one of these features are most appropriate for military or law enforcement use. Therefore, shotguns containing any of these features are not particularly suitable for nor readily adaptable to generally recognized sporting purposes such as hunting, trap, sporting clay, and skeet shooting. Each of these features and an analysis of each of the determinations are included within the main body of the report.

The purpose of this study is to establish criteria that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) will use to determine the importability of certain shotguns under the provisions of the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA).

A shotgun is defined by the GCA as “a weapon designed or redesigned, made or remade, and intended to be fired from the shoulder and designed or redesigned and made or remade to use the energy of an explosive to fire through a smooth bore either a number of ball shot or a single projectile for each single pull of the trigger.”

[18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(5).]

Shotguns are traditional hunting firearms and, in the past, have been referred to as bird guns or “fowling” pieces. They were designed to propel multiple pellets of shot in a particular pattern that is capable of killing the game that is being hunted. This design and type of ammunition limits the maximum effective long distance range of shotguns, but increases their effectiveness for small moving targets such as birds in flight at a close range. Additionally, shotguns have been used to fire slugs. A shotgun slug is a single metal projectile that is fired from the barrel. Slugs have been utilized extensively in areas where State laws have restricted the use of rifles for hunting. Additionally, many States have specific shotgun seasons for deer hunting and, with the reintroduction of wild turkey in many States, shotguns and slugs have found additional sporting application.

Shotguns are measured by gauge in the United States. The gauge number refers to the “number of equal-size balls cast from one pound of lead that would pass through the bore of a specific diameter.”

[The Shotgun Encyclopedia at 106.]

The largest commonly available gauge is 10 gauge (.0775 in. bore diameter).

Therefore, a 10 gauge shotgun will have an inside diameter equal to that of a sphere made from one-tenth of a pound of lead. By far, the most common gauges are 12 (0.729 in. diameter) and 20 (0.614 in. diameter). The smallest shotgun that is readily available is known as a “.410,” which is the diameter of its bore measured in inches. Technically, a .410 is a 67 gauge shotgun.

The GCA generally prohibits the importation of firearms into the United States.

[18 U.S.C. § 922(l).]

However, the statute exempts four narrow categories of firearms that the Attorney General shall authorize for importation. Originally enacted by Title IV of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 [Pub. Law 90-351 (June 19, 1968)], and amended by Title I of the GCA [Pub. Law 90-618 (October 22, 1968)] enacted that same year, this section provides, in pertinent part:

the Attorney General shall authorize a firearm . . . to be imported or brought into the United States . . . if the firearm . . . (3) is of a type that does not fall within the definition of a firearm as defined in section 5845(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 and is generally recognized as particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes, excluding surplus military firearms, except in any case where the Secretary has not authorized the importation of the firearm pursuant to this paragraph, it shall be unlawful to import any frame, receiver, or barrel of such firearm which would be prohibited if assembled. (Emphasis added)

[18 U.S.C. § 925(d)(3). In pertinent part, 26 U.S.C. § 5845(a) includes “a shotgun having a barrel or barrels of less than 18 inches in length.”]

This section addresses Congress’ concern that the United States had become a “dumping ground of the castoff surplus military weapons of other nations,” [90 P.L. 351 (1968)] in that it exempted only firearms with a generally recognized sporting purpose. In recognizing the difficulty in implementing this section, Congress gave the Secretary of the Treasury (now the Attorney General) the discretion to determine a weapon’s suitability for sporting purposes. This authority was ultimately delegated to what is now ATF. Immediately after discussing the large role cheap imported .22 caliber revolvers were playing in crime, the Senate Report stated:

[t]he difficulty of defining weapons characteristics to meet this target without discriminating against sporting quality firearms, was a major reason why the Secretary of the Treasury has been given fairly broad discretion in defining and administering the import prohibition.

[S. Rep. No. 1501, 90th Cong. 2d Sess. 38 (1968).]

Indeed, Congress granted this discretion to the Secretary even though some expressed concern with its breadth:

[t]he proposed import restrictions of Title IV would give the Secretary of the Treasury unusually broad discretion to decide whether a particular type of firearm is generally recognized as particularly suitable for, or readily adaptable to, sporting purposes. If this authority means anything, it permits Federal officials to differ with the judgment of sportsmen expressed through consumer preference in the marketplace....

[S. Rep. No. 1097, 90th Cong. 2d. Sess. 2155 (1968) (views of Senators Dirksen, Hruska, Thurmond, and Burdick). In Gun South, Inc. v. Brady, 877 F.2d 858, 863 (11th Cir. 1989), the court, based on legislative history, found that the GCA gives the Secretary “unusually broad discretion in applying section 925(d)(3).”]

Since that time, ATF has been responsible for determining whether firearms are generally recognized as particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes under the statute.

On December 10, 1968, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division of the Internal Revenue Service (predecessor to ATF) convened a “Firearm Advisory Panel” to assist with defining “sporting purposes” as utilized in the GCA. This panel was composed of representatives from the military, law enforcement, and the firearms industry. The panel generally agreed that firearms designed and intended for hunting and organized competitive target shooting would fall into the sporting purpose criteria. It was also the consensus that the activity of “plinking” was primarily a pastime and therefore would not qualify. Additionally, the panel looked at criteria for handguns and briefly discussed rifles. However, no discussion took place on shotguns given that, at the time, all shotguns were considered inherently sporting because they were utilized for hunting or organized competitive target competitions.

Then, in 1984, ATF organized the first large scale study aimed at analyzing the sporting suitability of certain firearms. Specifically, ATF addressed the sporting purposes of the Striker-12 and Streetsweeper shotguns. These particular shotguns were developed in South Africa as law enforcement, security and anti-terrorist weapons. These firearms are nearly identical 12-gauge shotguns, each with 12-round capacity and spring-driven revolving magazines. All 12 rounds can be fired from the shotguns within 3 seconds.

In the 1984 study, ATF ruled that the Striker-12 and the Streetsweeper were not eligible for importation under 925(d)(3) because they were not “particularly suitable for sporting purposes.” In doing this, ATF reversed an earlier opinion and specifically rejected the proposition that police or combat competitive shooting events were a generally accepted “sporting purpose.” This 1984 study adopted a narrow interpretation of organized competitive target shooting competitions to include the traditional target events such as trap and skeet. ATF ultimately concluded that the size, weight and bulk of the shotguns made them difficult to maneuver in traditional shooting sports and, therefore, these shotguns were not particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to these sporting purposes. At the same time, however, ATF allowed importation of a SPAS-12 variant shotgun because its size, weight, bulk and modified configuration were such that it was particularly suitable for traditional shooting sports.

[Private letter Ruling of August 9, 1989 from Bruce L. Weininger, Chief, Firearms and Explosives Division.]

The Striker-12 and Streetsweeper were later classified as “destructive devices” pursuant to the National Firearms Act.

[See ATF Rulings 94-1 and 94-2.]

In 1989, and again in 1998, ATF conducted studies to determine whether certain rifles could be imported under section 925(d)(3). The respective studies focused primarily on the application of the sporting purposes test to a type of firearm described as a “semiautomatic assault weapon.” In both 1989 and 1998, ATF was concerned that certain semiautomatic assault weapons had been approved for importation even though they did not satisfy the sporting purposes test.

In 1989, ATF announced that it was suspending the importation of several semiautomatic assault rifles pending a decision on whether they satisfied the sporting criteria under section 925(d)(3).

The 1989 study determined that assault rifles were a “type” of rifle that contained a variety of physical features that distinguished them from traditional sporting rifles. The study concluded that there were three characteristics that defined semiautomatic assault rifles:

(1) a military configuration (ability to accept a detachable magazine, folding/telescoping stocks, pistol grips, ability to accept a bayonet, flash suppressors, bipods, grenade launchers, and night sights);

(2) semiautomatic version of a machinegun;

(3) chambered to accept a centerfire cartridge case having a length of 2.25 inches or less.

[1989 Report and Recommendation on the ATF Working Group on the Importability of Certain Semiautomatic Rifles (1989 Study).]

The 1989 study then examined the scope of “sporting purposes“ as used in the statute. [Id. at 8.]

The study noted that “[t]he broadest interpretation could take in virtually any lawful activity or competition which any person or groups of persons might undertake. Under this interpretation, any rifle could meet the “sporting purposes” test. [Id.]

The 1989 study concluded that a broad interpretation would render the statute useless. The study therefore concluded that neither plinking nor “police/combat-type” competitions would be considered sporting activities under the statute. [Id. At 9.]

The 1989 study concluded that semiautomatic assault rifles were “designed and intended to be particularly suitable for combat rather than sporting applications.” [Id. At 12.]

With this, the study determined that they were not suitable for sporting purposes and should not be authorized for importation under section 925(d)(3).

The 1998 study was conducted after “members of Congress and others expressed concern that rifles being imported were essentially the same as semiautomatic assault rifles previously determined to be nonimportable” under the 1989 study. [1998 Study at 1.]

Specifically, many firearms found to be nonimportable under the 1989 study were later modified to meet the standards outlined in the study. These firearms were then legally imported into the country under section 925(d)(3). ATF commissioned the 1998 study on the sporting suitability of semiautomatic rifles to address concerns regarding these modified firearms.

The 1998 study identified the firearms in question and determined that the rifles shared an important feature—the ability to accept a large capacity magazine that was originally designed for military firearms. The report then referred to such rifles as Large Capacity Military Magazine rifles or “LCMM rifles.” [1998 Study at 16.]

The study noted that after 1989, ATF refused to allow importation of firearms that had any of the identified non-sporting features, but made an exception for firearms that possessed only a detachable magazine. Relying on the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban, the 1998 study noted that Congress “sent a strong signal that firearms with the ability to expel large amounts of ammunition quickly are not sporting.” [1998 Study at 3.]

The study concluded by adopting the standards set forth in the 1989 study and by reiterating the previous determination that large capacity magazines are a military feature that bar firearms from importation under section 925(d)(3).

[The 1994 Assault Weapons Ban expired Sept. 13, 2004, as part of the law's sunset provision.]

While ATF conducted the above mentioned studies on the sporting suitability of rifles, to date, no study has been conducted to address the sporting purposes and importability of shotguns. This study was commissioned for that purpose and to ensure that ATF complies with it statutory mandate under section 925(d)(3).

To conduct this study, the working group reviewed current shooting sports and the sporting suitability of common shotguns and shotgun features. At the outset, the working group recognized the importance of acknowledging the inherent differences between rifles, handguns and shotguns. These firearms have distinct characteristics that result in specific applications of each weapon. Therefore, in conducting the study, the working group generally considered shotguns without regard to technical similarities or differences that exist in rifles or handguns.

The 1989 and 1998 studies examined particular features and made sporting suitability determinations based on the generally accepted sporting purposes of rifles. These studies served as useful references because, in recent years, manufacturers have produced shotguns with features traditionally found only on rifles. These features are typically used by military or law enforcement personnel and provide little or no advantage to sportsmen.

Following a review of the 1989 and 1998 studies, the working group believed that it was necessary to first identify those activities that are considered legitimate “sporting purposes” in the modern era. While the previous studies determined that only “the traditional sports of hunting and organized competitive target shooting” would be considered “sporting,” [1998 Study at 16] the working group recognized that sporting purposes may evolve over time. The working group felt that the statutory language supported this because the term “generally recognized” modifies, not only firearms used for shooting activities, but also the shooting activities themselves. This is to say that an activity is considered “sporting” under section 925(d)(3) if it is generally recognized as such.

[ATF previously argued this very point in Gilbert Equipment Company , Inc. v. Higgins, 709 F.Supp. 1071, 1075 (S.D. Ala. 1989). The court agreed, noting, “according to Mr. Drake, the bureau takes the position.. .that an event has attained general recognition as being a sport before those uses and/or events can be ‘sporting purposes’ or ‘sports’ under section 925(d)(3). See also Declaration of William T. Drake, Deputy Director, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms.]

Therefore, activities that were “generally recognized” as legitimate “sporting purposes” in previous studies are not necessarily the same as those activities that are “generally recognized” as sporting purposes in the modern era. As stated above, Congress recognized the difficulty in legislating a fixed meaning and therefore gave the Attorney General the responsibility to make such determinations. As a result, the working group did not simply accept the proposition that sporting events were limited to hunting and traditional trap and skeet target shooting. In determining whether an activity is now generally accepted as a sporting purpose, the working group considered a broad range of shooting activities.

Once the working group determined those activities that are generally recognized as a “sporting purpose” under section 925(d)(3), it examined numerous shotguns with diverse features in an effort to determine whether any particular firearm was particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to those sports. In coming to a determination, the working group recognized that a shotgun cannot be classified as sporting merely because it may be used for a sporting purpose. During debate on the original bill, there was discussion about the meaning of the term "sporting purposes." Senator Dodd stated:

Here again I would have to say that if a military weapon is used in a special sporting event, it does not become a sporting weapon. It is a military weapon used in a special sporting event ....As I said previously the language says no firearms will be admitted into this country unless they are genuine sporting weapons.

[114 Cong. Rec. 27461-462 (1968).]

In making a determination on any particular feature, the working group considered State hunting laws, currently available products, scholarly and historical publications, industry marketing, and rules and regulations of organization such as the National Skeet Shooting Association, Amateur Trapshooting Association, National Sporting Clays Association, Single Action Shooting Society, International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), and the United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA). Analysis of these sources as well as a variety of shotguns led the working group to conclude that certain shotguns were of a type that did not meet the requirements of section 925(d)(3), and therefore, could not lawfully be imported.

In conducting the sporting purposes test on behalf of the Attorney General, ATF examines the physical and technical characteristics of a shotgun and determines whether those characteristics meet this statutory requirement. A shotgun’s suitability for a particular sport depends upon the nature and requirements inherent to that sport. Therefore, determining a “sporting purpose” was the first step in this analysis under section 925(d)(3) and is a critical step of the process.

A broad interpretation of “sporting purposes” may include any lawful activity in which a shooter might participate and could include any organized or individual shooting event or pastime. A narrow interpretation of “sporting purposes” would clearly result in a more selective standard governing the importation of shotguns.

Consistent with previous ATF decisions and case law, the working group recognized that a sport or event must “have attained general recognition as being a ‘sport,’ before those uses and/or events can be ‘sporting purposes’ or ‘sports’ under Section 925(d)(3).” [Gilbert at 1085.]

The statutory language limits ATF’s authority to recognize a particular shooting activity as a “sporting purpose,” and therefore requires a narrow interpretation of this term. As stated however, the working group recognized that sporting purposes may change over time, and that certain shooting activities may become “generally recognized” as such.

At the present time, the working group continues to believe that the activity known as “plinking” is not a generally recognized sporting purpose. There is nothing in the legislative history of the GCA to indicate that section 925(d)(3) was meant to recognize every conceivable type of activity or competition that might employ a firearm. Recognition of plinking as a sporting purpose would effectively nullify section 925(d)(3) because it may be argued that any shotgun is particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to this activity.

The working group also considered “practical shooting” competitions. Practical shooting events generally measure a shooter’s accuracy and speed in identifying and hitting targets while negotiating obstacle-laden shooting courses. In these competitions, the targets are generally stationary and the shooter is mobile, as opposed to clay target shooting where the targets are moving at high speeds mimicking birds in flight. Practical shooting consist of rifle, shotgun and handgun competitions, as well as “3-Gun” competitions utilizing all three types of firearm on one course. The events are often organized by local or national shooting organizations and attempt to categorize shooters by skill level in order to ensure competitiveness within the respective divisions. The working group examined participation in and popularity of practical shooting events as governed under formal rules such as those of the United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA) and International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC) to see if it is appropriate to consider these events a legitimate “sporting purpose” under section 925(d)(3).

The USPSA currently reports approximately 19,000 members that participate in shooting events throughout the United States. [See www.uspsa.org.]

While USPSA’s reported membership is within the range of members for some other shotgun shooting organizations [*], organizations involved in shotgun hunting of particular game such as ducks, pheasants and quail indicate significantly more members than any of the target shooting organizations. [**]

[* – Organization websites report these membership numbers: for the United States Practical Shooting Association, approx. 19,000; Amateur Trapshooting Association, over 35,000 active members; National Skeet Shooting Association, nearly 20,000 members; National Sporting Clays Association, over 22,000 members; Single Action Shooting Society, over 75,000 members.]

[** – Organization websites report these membership numbers: Ducks Unlimited, U.S adult 604,902 (Jan. 1, 2010); Pheasants/Quail Forever, over 130,000 North American members (2010) http://www.pheasantfest.org/page/1/PressReleaseViewer.jsp?pressReleaseId=12406.]

Because a determination on the sporting purpose of practical shooting events should be made only after an in-depth study of those events, the working group determined that it was not appropriate to use this shotgun study to make a definitive conclusion as to whether practical shooting events are “sporting” for purposes of section 925(d)(3). Any such study must include rifles, shotguns and handguns because practical shooting events use all of these firearms, and a change in position by ATF on practical shooting or “police/combat-type” competitions may have an impact on the sporting suitability of rifles and handguns. Further, while it is clear that shotguns are used at certain practical shooting events, it is unclear whether shotgun use is so prevalent that it is “generally recognized” as a sporting purpose. If shotgun use is not sufficiently popular at such events, practical shooting would have no effect on any sporting suitability determination of shotguns. Therefore, it would be impractical to make a determination based upon one component or aspect of the practical shooting competitions.

As a result, the working group based the following sporting suitability criteria on the traditional sports of hunting, trap and skeet target shooting.

The final step in our review involved an evaluation of shotguns to determine a “type” of firearm that is “generally recognized as particularly suitable or readily adaptable to sporting purposes.” Whereas the 1989 and 1998 studies were conducted in response to Congressional interest pertaining to a certain “type” of firearm, the current study did not benefit from a mandate to focus upon and review a particular type of firearm. Therefore, the current working group determined that it was necessary to consider a broad sampling of shotguns and shotgun features that may constitute a “type.”

Whereas rifles vary greatly in size, function, caliber and design, historically, there is less variation in shotgun design. However, in the past several years, ATF has witnessed increasingly diverse shotgun design. Much of this is due to the fact that some manufacturers are now applying rifle designs and features to shotguns. This has resulted in a type of shotgun that has features or characteristics that are based on tactical and military firearms. Following a review of numerous shotguns, literature, and industry advertisements, the working group determined that the following shotgun features and design characteristics are particularly suitable for the military or law enforcement, and therefore, offer little or no advantage to the sportsman. Therefore, we recognized that any shotgun with one or more of these features represent a “type” of firearm that is not “generally recognized as particularly suitable or readily adaptable to sporting purposes” and may not be imported under section 925(d)(3).

Shotgun stocks vary in style, but sporting stocks have largely resembled the traditional design. [Exhibit 1.] Many military firearms incorporate folding or telescoping stocks. The main advantage of this feature is portability, especially for airborne troops. These stocks allow the firearm to be fired from the folded or retracted position, yet it is difficult to fire as accurately as can be done with an open or fully extended stock. While a folding stock or telescoping stock makes it easier to carry the firearm, its predominant advantage is for military and tactical purposes. A folding or telescoping stock is therefore not found on the traditional sporting shotgun. Note that certain shotguns may utilize adjustable butt plates, adjustable combs, or other designs intended only to allow a shooter to make small custom modifications to a shotgun. These are not intended to make a shotgun more portable, but are instead meant to improve the overall “fit” of the shotgun to a particular shooter. These types of adjustable stocks are sporting and are, therefore, acceptable for importation.

A bayonet lug is generally a metal mount that allows the installation of a bayonet onto the end of a firearm. While commonly found on rifles, bayonets have a distinct military purpose. Publications have indicated that this may be a feature on military shotguns as well.

[A Collector’s Guide to United States Combat Shotguns at 156.]

It enables soldiers to fight in close quarters with a knife attached to their firearm. The working group discovered no generally recognized sporting application for a bayonet on a shotgun.

Flash suppressors are generally used on military firearms to disperse the muzzle flash in order to help conceal the shooter’s position, especially at night. Compensators are used on military and commercial firearms to assist in controlling recoil and the “muzzle climb” of the shotgun. Traditional sporting shotguns do not have flash suppressors or compensators. However, while compensators have a limited benefit for shooting sports because they allow the shooter to quickly reacquire the target for a second shot, there is no particular benefit in suppressing muzzle flash in sporting shotguns. Therefore, the working group finds that flash suppressors are not a sporting characteristic, while compensators are a sporting feature. However, compensators that, in the opinion of ATF, actually function as flash suppressors are neither particularly suitable nor readily adaptable to sporting purposes.

A magazine is an ammunition storage and feeding device that delivers a round into the chamber of the firearm during automatic or semiautomatic firing.

[Steindler’s New Firearms Dictionary at 164.]

A magazine is either integral (tube magazine) to the firearm or is removable (box magazine). A drum magazine is a large circular magazine that is generally detachable and is designed to hold a large amount of ammunition.

The 1989 Study recognized that virtually all modern military firearms are designed to accept large, detachable magazines. The 1989 Study noted that this feature provides soldiers with a large ammunition supply and the ability to reload rapidly. The 1998 Study concurred with this and found that, for rifles, the ability to accept a detachable large capacity magazine was not a sporting feature. The majority of shotguns on the market today contain an integral “tube” magazine. However, certain shotguns utilize removable box magazine like those commonly used for rifles.

[See Collector’s Guide to United States Combat Shotguns at 156-7, noting that early combat shotguns were criticized because of their limited magazine capacity and time consuming loading methods.]

In regard to sporting purposes, the working group found no appreciable difference between integral tube magazines and removable box magazines. Each type allowed for rapid loading, reloading, and firing of ammunition. For example, “speed loaders” are available for shotguns with tube-type magazines. These speed loaders are designed to be preloaded with shotgun shells and can reload a shotgun with a tube-type magazine in less time than it takes to change a detachable magazine.

However, the working group determined that magazines capable of holding large amounts of ammunition, regardless of type, are particularly designed and most suitable for military and law enforcement applications. The majority of state hunting laws restrict shotguns to no more than 5 rounds. [Exhibit 2.] This is justifiable because those engaged in sports shooting events are not engaging in potentially hostile or confrontational situations, and therefore do not require the large amount of immediately available ammunition, as do military service members and police officers.

Finally, drum magazines are substantially wider and have considerably more bulk than standard clip-type magazines. They are cumbersome and, when attached to the shotgun, make it more difficult for a hunter to engage multiple small moving targets. Further, drum magazines are generally designed to contain more than 5 rounds. Some contain as many as 20 or more rounds. [Exhibit 3.] While such magazines may have a military or law enforcement application, the working group determined that they are not useful for any generally recognized sporting purpose. These types of magazines are unlawful to use for hunting in most states, and their possession and manufacture are even prohibited or restricted in some states. [See, e.g., Cal Pen Code § 12020; N.J. Stat. § 2C:39-9.]

Grenade launchers are incorporated into military firearms to facilitate the launching of explosive grenades. Such launchers are generally of two types. The first type is a flash suppressor designed to function as a grenade launcher. The second type attaches to the barrel of the firearm either by screws or clamps. Grenade launchers have a particular military application and are not currently used for sporting purposes.

This refers to a mounting rail system for small arms upon which firearm accessories and features may be attached. This includes scopes, sights, and other features, but may also include accessories or features with no sporting purpose, including flashlights, foregrips, and bipods. Rails on the sides and underside of shotguns—including any accessory mount—facilitate installation of certain features lacking any sporting purpose. However, receiver rails that are installed on the top of the receiver and barrel are readily adaptable to sporting purposes because this facilitates installation of optical or other sights.

Shotguns are generally configured with either bead sights, iron sights or optical sights, depending on whether a particular sporting purpose requires the shotgun to be pointed or aimed. [NRA Firearms Sourcebook at 178.] Bead sights allow a shooter to “point” at and engage moving targets at a short distance with numerous small projectiles, including birds, trap, skeet and sporting clays. Iron and optical sights are used when a shooter, firing a slug, must “aim” a shotgun at a target, including deer, bear and turkeys. [Id.] Conversely, many military firearms are equipped with sighting devices that utilize available light to facilitate night vision capabilities. Devices or optics that allow illumination of a target in low-light conditions are generally for military and law enforcement purposes and are not typically found on sporting shotguns because it is generally illegal to hunt at night.

Sporting shotguns, 12 gauge and smaller, are lightweight (generally less than 10 pounds fully assembled), [*] and are balanced and maneuverable.

[* – Shotgun Encyclopedia 2001 at 264.]

This aids sportsmen by allowing them to carry the firearm over long distances and rapidly engage a target. Unlike sporting shotguns, military firearms are larger, heavier, and generally more rugged. This design allows the shotguns to withstand more abuse in combat situations.

Sporting shotguns are generally no more than 3 inches in width or more than 4 inches in depth. This size allows sporting shotguns to be sufficiently maneuverable in allowing hunters to rapidly engage targets. Certain combat shotguns may be larger for increased durability or to withstand the stress of automatic fire. The bulk refers to the fully assembled shotgun, but does not include magazines or accessories such as scopes or sights that are used on the shotgun. For both width and depth, shotguns are measured at the widest points of the action or housing on a line that is perpendicular to the center line of the bore. Depth refers to the distance from the top plane of the shotgun to the bottom plane of the shotgun. Width refers to the length of the top or bottom plane of the firearm and measures the distance between the sides of the shotgun. Neither measurement includes the shoulder stock on traditional sporting shotgun designs.

While sporting shotguns differ in the style of shoulder stock, they are remarkably similar in fore-end design.

[See Exhibit 1. See generally NRA Firearms Sourcebook at 121-2.]

Generally, sporting shotguns have a fore-grip with which the shooter’s forward hand steadies and aims the shotgun. Recently, however, some shooters have started attaching forward pistol grips to shotguns. These forward pistol grips are often used on tactical firearms and are attached to those firearms using the integrated rail system. The ergonomic design allows for continued accuracy during sustained shooting over long periods of time. This feature offers little advantage to the sportsman. Note, however, that the working group believes that pistol grips for the trigger hand are prevalent on shotguns and are therefore generally recognized as particularly suitable for sporting purposes. [See Exhibit 1.]

While the features listed above are the most common non-sporting shotgun features, the working group recognizes that other features, designs, or characteristics may exist. Prior to importation, ATF will classify these shotguns based upon the requirements of section 925(d)(3). The working group expects the continued application of unique features and designs to shotguns that may include features or designs based upon traditional police or military tactical rifles. However, even if a shotgun does not have one of the features listed above, it may be considered “sporting” only if it meets the statutory requirements under section 925(d)(3). Further, the simple fact that a military firearm or feature may be used for a generally recognized sporting purposes is not sufficient to support a determination that it is sporting under 925(d)(3). Therefore, as required by section 925(d)(3), in future sporting classifications for shotguns, ATF will classify the shotgun as sporting only if there is evidence that its features or design characteristics are generally recognized as particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to generally recognized sporting purposes.

The fact that a firearm or feature was initially designed for military or tactical applications, including offensive or defensive combat, may indicate that it is not a sporting firearm. This may be overcome by evidence that the particular shotgun or feature has been so regularly used by sportsmen that it is generally recognized as particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes. Such evidence may include marketing, industry literature and consumer articles, scholarly and historical publications, military publications, the existence of State and local statutes and regulations limiting use of the shotgun or features for sporting purposes, and the overall use and the popularity of such features or designs for sporting purposes according to hunting guides, shooting magazines, State game commissioners, organized competitive hunting and shooting groups, law enforcement agencies or organizations, industry members and trade associations, and interest and information groups. Conversely, a determination that the shotgun or feature was originally designed as an improvement or innovation to an existing sporting shotgun design or feature will serve as evidence that the shotgun is sporting under section 925(d)(3). However, any new design or feature must still satisfy the sporting suitability test under section 925(d)(3) as outlined above.

The Attorney General and ATF are not limited to these factors and therefore may consider any other factor determined to be relevant in making this determination. The working group recognizes the difficulty in applying this standard but acknowledges that Congress specifically intended that the Attorney General perform this function. Therefore, the working group recommends that sporting determinations for shotguns not specifically addressed by this study be reviewed by a panel pursuant to ATF orders, policies and procedures, as appropriate.

The purpose of section 925(d)(3) is to provide a limited exception to the general prohibition on the importation of firearms without placing “any undue or unnecessary Federal restrictions or burdens on law-abiding citizens with respect to the acquisition, possession, or use of firearms...” [90 P.L. 351 (1968).]

Our determinations will in no way preclude the importation of true sporting shotguns. While it will certainly prevent the importation of certain shotguns, we believe that those shotguns containing the enumerated features cannot be fairly characterized as “sporting” shotguns under the statute. Therefore, it is the recommendation of the working group that shotguns with any of the characteristics or features listed above not be authorized for importation.

“Straight”

or “English” style stock (Ruger Red Label)

“Pistol

grip” style stock (Browning Citori)

“Pistol

grip” style stock (Mossberg 935 Magnum Turkey)

“Thumbhole”

style stock (Remington SP-10)

Stock

with Separate Pistol Grip

|

State |

Gauge |

Mag Restriction / plugged with one piece filler requiring disassembly of gun for removal |

Attachments |

Semi-Auto |

Other |

|

Alabama |

10 gauge or smaller; |

(Species specific) |

|

|

Shotgun/rifle combinations (drilling) permitted |

|

Alaska |

10 gauge or smaller |

|

|

|

|

|

Arizona |

10 gauge or smaller |

5 shells |

|

|

|

|

Arkansas |

≤ 10 gauge; some zones ≥ .410; ≥ 20 gauge for bear |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

California |

≤ 10 gauge; Up to 12 gauge in some areas |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Colorado |

≥ 20 gauge; Game Mammals ≤ 10 gauge |

3 shells |

|

|

|

|

Connecticut |

≤ 10-gauge |

(Species specific) |

telescopic sights |

|

|

|

Delaware |

20, 16, 12, 10 gauge |

3 shells |

Muzzleloaders may be equipped with scopes |

|

large game training course - Students in optional proficiency qualification bring their own pre-zeroed, ≥ .243 , scoped shotgun |

|

Florida |

Muzzleloading firing ≥ 2 balls ≥ 20-gauge; Migratory birds ≤ 10-gauge; opossums -single-shot .41 -gauge shotguns |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Georgia |

≥ 20-gauge; Waterfowl ≤ 10-gauge |

5 shells |

Scopes are legal |

|

|

|

Hawaii |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Idaho |

|

|

some scopes allowed |

|

no firearm that, in combination with a scope, sling and/or any attachments, weighs more than 16 pounds |

|

Illinois |

20 - 10 gauge; no .410 or 28 gauge allowed |

3 shells |

|

|

|

|

Indiana |

|

(Species specific) |

Laser sights are legal |

|

|

|

Iowa |

10-, 12-, 16-, and 20-gauge |

|

|

|

|

|

Kansas |

≥ 20 gauge; ≤ 10 gauge, |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Kentucky |

up to and including 10-gauge, includes .410- |

(Species specific) |

Telescopic sights (scopes) |

|

|

|

Louisiana |

≤ 10 gauge |

3 shells |

Nuisance Animals; infrared, laser sighting devices, or night vision devices |

|

|

|

Maine |

10 - 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

may have any type of sights, including scopes |

Auto-loading illegal if hold more than 6 cartridges |

|

|

Maryland |

Muzzle loading ≥ 10 gauge ; Shotgun ≤ 10-gauge |

(Species specific) |

may use a telescopic sight on muzzle loading firearm |

|

|

|

Massachusetts |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Michigan |

any gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

Illegal: semi-automatic holding > 6 shells in barrel and magazine combined |

|

|

Minnesota |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Mississippi |

any gauge |

(Species specific) |

Scopes allowed on primitive weapons |

|

|

|

Missouri |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Montana |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Nebraska |

≥ 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

Illegal: semi-automatic holding > 6 shells in barrel and magazine combined |

|

|

Nevada |

≤ 10 gauge; ≥ 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

10 - 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

New Jersey |

≤ 10 gauge; ≥ 20 gauge; or .410 caliber |

(Species specific) |

Require adjustable open iron, peep sight or scope affixed if hunting with slugs. Telescopic sights Permitted |

|

|

|

New Mexico |

≥ 28 gauge, ≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

New York |

Big game ≥ 20 gauge |

|

scopes allowed |

No semi-automatic firearm with a capacity to hold more than 6 rounds |

|

|

North Carolina |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

North Dakota |

≥ 410 gauge; no ≤ 10 gauge |

3 shells (repealed for migratory birds) |

|

|

|

|

Ohio |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Oklahoma |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Oregon |

≤ 10 gauge; ≥ 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

Scopes (permanent and detachable), and sights allowed for visually impaired |

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

≤ 10 gauge; ≥ 12 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Rhode Island |

10, 12, 16, or 20-gauge |

5 shells |

|

|

|

|

South Carolina |

|

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

South Dakota |

(Species specific) ≤ 10 gauge |

5 shells |

|

No auto-loading firearm holding > 6 cartridges |

|

|

Tennessee |

Turkey: ≥ 28 gauge |

(Species specific) |

May be equipped with sighting devices |

|

|

|

Texas |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

scoping or laser sighting devices used by disabled hunters |

|

|

|

Utah |

≤ 10 gauge; ≥ 20 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Vermont |

≥ 12 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Virginia |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Washington |

≤ 10 gauge |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

West Virginia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wisconsin |

10, 12, 16, 20 and 28 gauge; no .410 shotgun for deer/bear |

(Species specific) |

|

|

|

|

Wyoming |

|

|

|

|

no relevant restrictive laws concerning shotguns |

|

State |

Source |

Semi-Auto Restrictions |

Attachments |

Prohibited* (in addition to possession of short-barrel or sawed-off shotguns by non-authorized persons, e.g., law enforcement officers for official duty purposes) |

|

Alabama |

Alabama Code, title 13: |

|

|

|

|

Alaska |

Alaska Statutes 11.61.200.(h) |

|

|

|

|

Arizona |

Arizona Rev. Statutes 13-3101.8. |

single shot |

silencer prohibited |

|

|

Arkansas |

Arkansas Code Title 5, Chapter 73. |

|

|

|

|

California |

California Penal Code, Part 4.12276. and San Diego Municipal Code 53.31. |

San Diego includes under "assault weapon," any shotgun with a magazine capacity of more than 6 rounds |

|

"Assault weapons": Franchi SPAS 12 and LAW 12; Striker 12; Streetsweeper type S/S Inc. ; semiautomatic shotguns having both a folding or telescoping stock and a pistol grip protruding conspicuously beneath the action of the weapon, thumbhole stock, or vertical handgrip; semiautomatic shotguns capable of accepting a detachable magazine; or shotguns with a revolving cylinder. |

|

Colorado |

2 CCR 406-203 |

|

|

|

|

Connecticut |

Connecticut Gen. Statutes 53-202a. |

|

|

"Assault weapons": Steyr AUG; Street Sweeper and Striker 12 revolving cylinder shotguns |

|

D.C |

7-2501.01. |

|

|

|

|

Delaware |

7.I.§ 711. |

|

|

7.I.§ 711. Hunting with automatic-loading gun prohibited; penalty (a) No person shall hunt for game birds or game animals in this State, except as authorized by state-sanctioned federal depredation/conservation orders for selected waterfowl species, with or by means of any automatic-loading or hand-operated repeating shotgun capable of holding more than 3 shells, the magazine of which has not been cut off or plugged with a filler incapable of removal through the loading end thereof, so as to reduce the capacity of said gun to not more than 3 shells at 1 time, in the magazine and chamber combined. (b) Whoever violates this section shall be guilty of a class C environmental misdemeanor. (c) Having in one's possession, while in the act of hunting game birds or game animals, a gun that will hold more than 3 shells at one time in the magazine and chamber combined, except as authorized in subsection (a) of this section, shall be prima facie evidence of violation of this section. |

|

Florida |

Florida statutes, Title XLVI.790.001. |

|

|

|

|

Georgia |

|

|

|

|

|

Hawaii |

Hawaii Rev. Statutes, Title 10., 134-8. |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

|

Idaho |

Idaho Code, 18-3318. |

|

|

|

|

Illinois |

Code of Ordinances, City of Aurora 29-43. |

Aurora includes under "assault weapon," any shotgun with a magazine capacity of more than 5 rounds |

|

"Assault weapons": Street Sweeper and Striker 12 revolving cylinder shotguns or semiautomatic shotguns with either a fixed magazine with a capacity over 5 rounds or an ability to accept a detachable magazine and has at least a folding / telescoping stock or a pistol grip that protrudes beneath the action of firearm and which is separate and apart from stock |

|

Indiana |

Indiana Code 35-47-1-10. and Municipal Code of the City of South Bend 13-95. |

|

South Bend under "assault weapon" firearms which have threads, lugs, or other characteristics designed for direct attachment of a silencer, bayonet, flash suppressor, or folding stock; as well as any detachable magazine, drum, belt, feed strip, or similar device which can be readily made to accept more than 15. rounds |

South Bend includes under "assault weapon," any shotgun with a magazine capacity of more than 9 rounds |

|

Iowa |

Iowa Code, Title XVI. 724.1. |

|

|

Includes as an offensive weapon, "a firearm which shoots or is designed to shoot more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger" |

|

Kansas |

|

|

|

|

|

Kentucky |

Kentucky Revised Statutes- 150.360 |

|

|

|

|

Louisiana |

Louisiana RS 56:116.1 |

|

|

|

|

Maine |

Maine Revised Statutes 12.13.4.915.4.§11214. F. |

|

|

|

|

Maryland |

Maryland Code 5-101. |

|

|

"Assault weapons": F.I.E./Franchi LAW 12 and SPAS 12 assault shotgun; Steyr-AUG-SA semi-auto; Holmes model 88 shotgun; Mossberg model 500 Bullpup assault shotgun; Street sweeper assault type shotgun; Striker 12 assault shotgun in all formats; Daewoo USAS 12 semi-auto shotgun |

|

Massachusetts |

Massachusetts Gen L. 140.121. |

under "assault weapon": any shotgun with (fixed or detachable) magazine capacity of more than 5 rounds |

|

"Assault weapons": revolving cylinder shotguns, e.g., Street Sweeper and Striker 12; also "Large capacity weapon" includes any semiautomatic shotgun fixed with large capacity feeding device (or capable of accepting such), that uses a rotating cylinder capable of accepting more than 5 shells |

|

Michigan |

II.2.1. (2) |

|

|

|

|

Minnesota |

Minnesota Statutes 624.711 |

|

|

"Assault weapons": Street Sweeper and Striker-12 revolving cylinder shotgun types as well as USAS-12 semiautomatic shotgun type |

|

Mississippi |

Mississippi Code 97-37-1. |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

|

Missouri |

Code of State Regulations 10-7.410(1)(G) |

|

|

|

|

Montana |

|

|

|

|

|

Nebraska |

Nebraska Administrative Code Title 163 Chapter 4 001. |

|

|

|

|

Nevada |

Nevada Revised Statutes 503.150 1. |

|

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

|

|

|

|

|

New Jersey |

New Jersey Statutes 23:4-13. and 23:444. and New Jersey Rev. Statutes 2C39-1.w. |

magazine capacity of no more than 5 rounds |

|

"Assault weapons": any shotgun with a revolving cylinder, e.g. "Street Sweeper" or "Striker 12" Franchi SPAS 12 and LAW 12 shotguns or USAS 12 semi-automatic type shotgun; also any semi-automatic shotgun with either a magazine capacity exceeding 6 rounds, a pistol grip, or a folding stock |

|

New Mexico |

New Mexico Administrative Code 19.31.6.7H., 19.31.11.10N. , 19.31.13.10M. and 19.31.17.10N. |

|

|

|

|

New York |

New York Consolidated Laws 265.00. 22. and Code of the City of Buffalo 1801B. |

magazine capacity of no more than 5 rounds |

sighting device making a target visible at night may classify a shotgun as an assault weapon |

"Assault weapons": Any semiautomatic shotgun with at least two of the following:folding or telescoping stock;pistol grip that protrudes conspicuously beneath the action of the weapon;fixed magazine capacity in excess of five rounds;an ability to accept a detachable magazine; or any revolving cylinder shotguns, e.g., Street Sweeper and Striker 12; Buffalo 1801B. Assault Weapon:(2) A center-fire rifle or shotgun which employs the force of expanding gases from a discharging cartridge to chamber a fresh round after each single pull of the trigger, and which has:(a) A flash suppressor attached to the weapon reducing muzzle flash;(c) A sighting device making a target visible at night;(d) A barrel jacket surrounding all or a portion of the barrel, to dissipate heat therefrom; or(e) A multi-burst trigger activator.(3) Any stockless pistol grip shotgun. |

|

North Carolina |

North Carolina Gen. Statutes 14-288.8 |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

|

North Dakota |

North Dakota Century Code 20.1-01-09. Section 20.1-04-10, SHOTGUN SHELLHOLDING CAPACITY RESTRICTION, repealed/eliminated |

|

|

|

|

Ohio |

Ohio Rev. Code 2923.11. and Columbus City Codes 2323.11. |

magazine capacity of no more than 5 rounds |

|

semiautomatic shotgun that was originally designed with or has a fixed magazine or detachable magazine with a capacity of more than five rounds. Columbus includes under "Assault weapon" any semi-automatic shotgun with two or more of the following: pistol grip that protrudes conspicuously beneath the receiver of the weapon; folding, telescoping or thumbhole stock; fixed magazine capacity in excess of 5 standard 2-3/4, or longer, rounds; or ability to accept a detachable magazine; also any shotgun with revolving cylinder |

|

Oklahoma |

|

|

|

|

|

Oregon |

Oregon Rev. Statutes 166.272. |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

|

Pennsylvania |

Title 34 Sec. 2308. (a)(4) and (b)(1) |

|

|

|

|

Rhode Island |

Rule 7, Part III, 3.3 and 3.4 |

|

|

|

|

South Carolina |

SECTION 50-11-310. (E) and ARTICLE 3. SUBARTICLE 1. 123 40 |

|

|

|

|

South Dakota |

South Dakota Codified Laws 22,1,2, (8) |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

|

|

|

Texas |

|

|

|

|

|

Utah |

Utah Administrative Code R657-5-9. (1), R657-6-6. (1) and R657-9-7. |

|

|

|

|

Vermont |

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia |

Virginia Code 18.2-308. |

magazine capacity no more than 7 rounds (not applicable for hunting or sport shooting) |

|

"Assault weapons": Striker 12's commonly called a "streetsweeper," or any semi-automatic folding stock shotgun of like kind with a spring tension drum magazine capable of holding twelve shotgun shells prohibited |

|

Washington |

Washington Administrative Code 232-12047 |

|

|

|

|

West Virginia |

West Virginia statute 8-12-5a. |

|

|

|

|

Wisconsin |

Wisconsin Administrative Code - NR 10.11 and NR 10.12 |

|

|

|

|

Wyoming |

Wyoming Statutes, Article 3. Rifles and Shotguns [Repealed] and 23-3-112. |

|

silencer prohibited |

|

Sporting

Sporting

Non-Sporting

Non-Sporting

Depth refers to the distance from the top plane of the shotgun to the bottom plane of the shotgun. Depth measurement “A” below is INCORRECT; it includes the trigger guard which is not part of the frame or receiver. Depth measurement “B” below is CORRECT; it measures only the depth of the frame or receiver:

Width refers to the length of the top or bottom pane of the firearm and measures the distance between the sides of the shotgun. Width measurement “A” below is CORRECT; it measures only the width of the frame or receiver. Width measurement “B” below is INCORRECT; it includes the charging handle which is not part of the frame or receiver: